Winning on Healthcare Cost and Losing on Healthcare

In today's New York Times, David Brooks* celebrates possibly durable reductions in healthcare cost inflation. He writes that many things, including bundled pricing for hip replacement, are a good thing, "at least fiscally." But what about healthcare?

Surgeo's technological lead serves as a perfect illustration of the confusion around cost and care. When she joined the team, she had a pretty expensive COBRA health insurance. When that lapsed, we got her regular old health insurance with premiums that cost even more than COBRA. So so much for cost -- for the consumer -- going down. To make it worse, she's been unable to get an appointment to see a primary doctor. This has been going on for a year. So yes, her insurer may be seeing less healthcare cost, but that's because she can't get in to see a doctor, whose services would cost the insurer money. The payer wins. Kim loses.

As a society, what we want is not less care cost but more care. So addressing the first without attending to the second is self-defeating. Brooks seems to know this, which probably explains his nod to healthcare: "many entrepreneurs who are providing innovations that maintain current quality of care but at lower cost." That casual assertion has no real teeth behind it and loses any validity from the very fundamental problem that most subject experts -- not to mention "many entrepreneurs" -- have no idea how to quantify quality. So even if healthcare cost inflation is really durably down, there is no support for the idea that healthcare, let alone healthcare quality, is being maintained.

What we should be asking ourselves is how we can do more with less. How do we provide the same healthcare or more healthcare for fewer dollars? There are many answers, starting with teaching hospital financial officers how cost-plus-margin pricing and activity based costing work. It sounds flippant to say this, but our experience with hospital financial officers in many regions of the United States is that hand-me-down "allowed amount" pricing has left them completely dissociated with the actual costs of actual supplies and labor. So when you ask them to price their services what you get is a healthcare answer to deer in headlights. This costs us plenty because valuable assets sit idly on the sidelines of the market. For a little more on this, see this presentation by our CEO to the Galen Institute, in which he describes the potential to reduce costs by providing more, not less, access to care. Of course, we can also consider the obvious other thing that nobody wants to talk about: reining in the drivers of defensive medicine.

There is also the notion that free markets can help. This is why one might consider allowing doctors in one state to help patients in another. States rights? Sure, but states have reciprocity for driving licenses. Why not medical licenses? Why not permit a doctor in Kansas City, Kansas to help a patient in Kansas City, Missouri?

Here's another free market idea: have a free market. Have a market in which quality and cost are presented to the consumer. That's the idea behind Kim's technology and it's already working. For example, a urologist in Houston who recently joined Surgeo for penile implant surgery, a treatment for erectile dysfunction, looked at the prices already posted and adjusted his prices down to stay competitive. Same with a surgeon in Austin who recently joined for total knee replacement, a treatment for arthritis. His package, in which the facility also looked first at Surgeo's other choices, is markedly lower in price compared with what is otherwise available. Free markets work and the resulting efficiency can help overcome economic barriers for many.

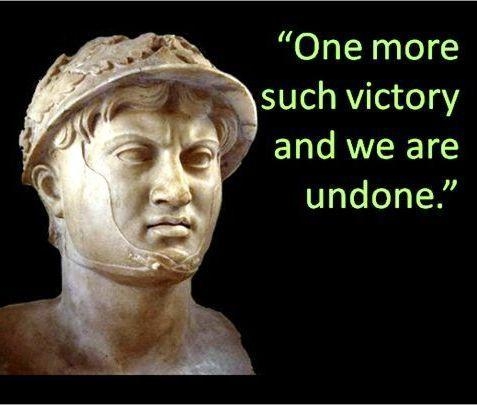

The Greek general Pyrrhus won battles but paid heavily, so much so that he reportedly said "one more such victory and we are undone." If we win our battles to reduce cost, will the price in care be our undoing?

*David Brooks article can be found here.